Writing a Simple Browser Game in Elm

TL;DR : This week I built a little spaceship game using Elm! You can play the game here (it probably won't work well on mobile or if you have a tiny screen) and see the source code here.

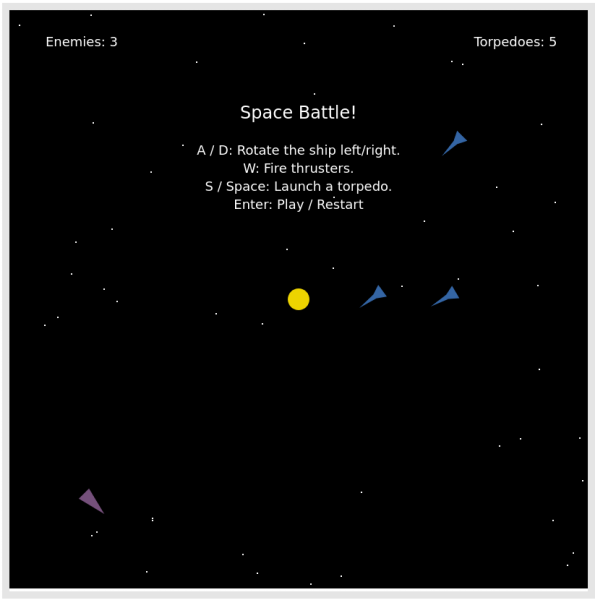

Here's a screenshot:

Context

This was my last week at Recurse Center; after Labor Day, I head back to full time work as a data engineer. One of my main RC projects, tidy-email, is waiting on some upstream changes on OPAM before it can be released. In light of all this, I decided to work on a short term project this week, and learn a bit of Elm.

My reasons for learning Elm are twofold. First, I think this technology is a great example of how to make strongly typed functional programming accessible to a wider audience. It's worth studying just for the sake of examining how ideas are presented, because I can re-use those skills to build user-friendly OCaml projects. Second, the "Elm Architecture" is widely used in front-end programming and I'd like to fill in some of the gaps in my front-end skill-set.

Defining the Project

I wanted this week's project to be small in scope and entertaining, so I decided to build a game similar to the 1962 game Spacewar!, written for the PDP-1 at MIT. You can read more about this game here and play an emulated version here.

Spacewar! features two rocket ships orbiting a star; the objective is to destroy the other player's ship by shooting it with a torpedo. The star exerts a gravitational pull on the two rockets, which complicates the ship's trajectories. A player that gets too close to the star loses. Player's that fly off the screen reappear on the opposite side, just like in Asteroids.

After playing with Spacewar! for a bit, I decided on the following rules for my game:

- The game should be single player instead of two player, with simple AI opponents.

- The player's should have a finite number of torpedoes, which replenish as they are used.

- The AI opponents should be able to shoot their own torpedoes at the player.

- Both the player and torpedoes should be influenced by gravity.

- There should be a display at the top of the screen tracking how many torpedoes the player has left and how many enemies they need to destroy.

- The player can lose by colliding with the sun, a torpedo, or an enemy.

Getting set up with Elm

I was quite impressed with how simple it was to get set up with

elm. There is a single executable that handles compiling Elm source

files, downloading dependencies from the internet, and serving an Elm

repl.

I read Beginning Elm to get a feel for the language. If you're coming to Elm from another strongly typed language like OCaml or Haskell, this guide is a pretty fast read. I appreciated that it provided chapters on the Elm architecture and how to make requests against a JSON API, so that I could jump right to those topics and start learning what I wanted to know.

I also found the online code editor Ellie quite helpful for running little experiments without installing anything, especially as I wanted to learn more about the elm-canvas library.

The main Elm documentation page provided a concise overview of the graphics package I wanted to use. Overall, I was quite happy with the quality of the documentation, though I did encounter a number of dead links on stack overflow.

I used VSCode with the Elm extension for my development work. This

was straightforward to install. Syntax and error highlighting worked

fine. I found the error highlighter to be quite aggressive. Part way

through adding a new function definition, the highlighter would mark

the entire source file as a single error, which was distracting. I

didn't bother to get live-reloading working because the project was so

small, but this would've been nice to have.

Thoughts on the Elm Architecture

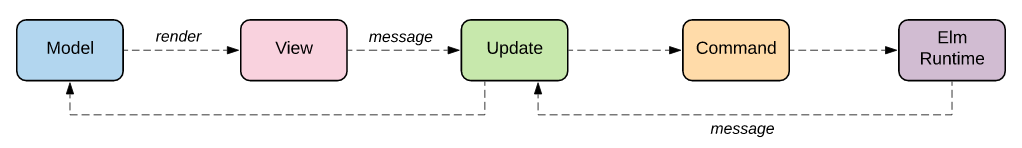

The Elm Architecture is worth expanding on a bit, and is summed up by the following diagram in Beginning Elm:

The Elm runtime is responsible for handling all side-effects, so that Elm programmers only need to work with pure functions and immutable data. To define the application, we provide the runtime with a handful of important definitions:

- A model that defines the state of the game at a moment in time.

- An initial model state, to be used when the app loads.

- A view function, that explains how to render the model in the browser.

- An update rule, that explains how to transform one model into another model based on inputs from the runtime.

- Finally, any subscriptions the app needs. In my case, the app subscribes to events from the keyboard and events from a timer, and these events dictate how to update the model.

I found that separating effectful code from pure code was very

convenient. It greatly simplified reasoning about my game logic. I

found that it natural to express different "game rules" in terms of

transformations on the Model, like this:

removeOldTorpedos : Model -> Model

removeOldTorpedos model =

let torpedoLifetime = 60 * 2 in -- ~ 2 seconds

let isLive b = model.time - b.created < torpedoLifetime in

{model | torpedos = List.filter isLive model.torpedos}

Developer Experience

Building a game in Elm was quite pleasant. The compiler's error messages are easy to interpret and the type system enables aggressive refactoring that would have been difficult for me to do in JavaScript. I found it quite easy to evolve my design as I worked and I didn't need to refer back to Beginning Elm or the documentation very often.

Overall I found Elm much easier to understand than rescript. I think this was in part because there are better-established conventions about how to build with Elm, and rescript is newer. I also found Elm's syntax easier to understand coming from OCaml than the JS/OCaml hybrid syntax in rescript.

I started the project with a very simple goal: Display a static scene with a background of stars, a yellow sun at the center, and two space ships. From there, I started to add simple physics, the ability to respond to keyboard events, and a simple collision detection system.

I really enjoyed how the compiler enabled me to explore "what-if" scenarios, like "What if I wanted to make the torpedoes change colors over time?". I found myself working in this cycle:

- Ask a what-if question.

- Change the data model to support that question.

- Fix the errors identified by the compiler.

- Compile.

- Try the game and reflect on whether it was more fun.

This tight development loop allowed me to spend most of my time "discovering" the right definitions for my game rather than fighting with confusing JavaScript bugs. Once I had a canvas and keyboard inputs working (which required a bit of research), the game came together quite quickly.

Conclusion

Fundamentally, I think Elm was easy to start using for two reasons:

- It cleanly separates pure computations from ones with side effects, via the Elm Architecture.

- The Elm team spent time making the tools easy to use and created well-written tutorials explaining the language.

This is definitely a tool I'd consider using for future front-end work and I'd recommend it to other developers who are interested in exploring strongly typed functional programming for the first time.

Feedback

If you found this post useful (or conversely, think that the advice here is bad), send me an email. My contact information is listed on the About page.